I.

When I go to check my PO box, I am literally running by the time I enter the building. My box is in the main post office in downtown Minneapolis, a long, squat building like an Art Deco fortress on the Mississippi riverfront. It was built in 1934 and has a gloriously cavernous, three-hundred-plus-foot-long lobby, and striding in there is like entering a movie set, honest to God, a dead ringer for city hall in a Batman flick or a brutal capitalist's corporate headquarters in an Orson Welles film, what with all the terrazzo floors and inlayed marble details on the walls and the little business-windows with brass bars and surrounds, like the kind you see at old-fashioned train station ticket counters. Stretching the entire length of the lobby is an immaculate brass light fixture, supposedly the longest in the world.

Even today, when some of those little brass-barred windows are boarded up, the place is beguilingly grand, alive with that elegant, Machine Age swagger that makes Art Deco so alluring. It's a thrill, it's a high, to walk in there. No lie.

But for me, it's not the aesthetics that make my heart race, at least not

just the aesthetics. Most of all, it's the task at hand.

I've got mail. Real mail. Letters and aerograms and postcards that begin, "Hello, stranger." And in our own ever-connected era--a truer Machine Age than any prior claimants to that title--that little bit of tactile, handwritten, hand-delivered personal communication is enough to make me sprint and punch the air and grin a big, giddy grin. (You think I am exaggerating for effect but somewhere, I'm sure, there are YouTube videos uploaded from the Minneapolis post office security cameras, soon-to-be-viral images of a bespectacled mail-nerd doing his happy dance.)

The fact that people--

strangers--keep sending me letters, many of them with notes about how much they miss getting real mail, makes me realize that I am very far from the only one thinking about this or doing something to keep it going.

II.

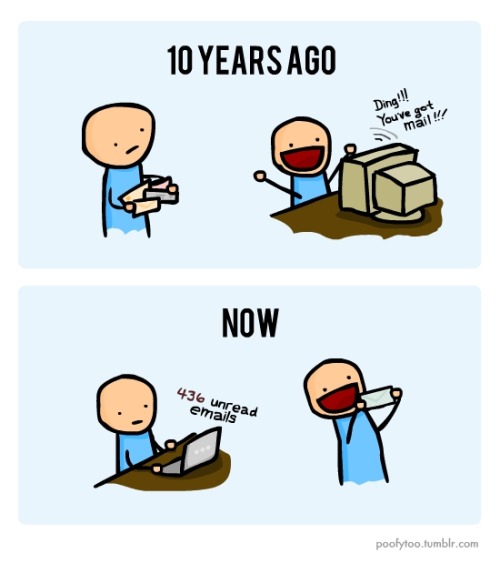

This cartoon has been making the rounds on the internet. Various friends of mine and the Oxford English Dictionary, among many, many others, have posted it on their Facebook pages.

Yeah. Exactly.

III.

At what point is a trend a trend? It's tempting to see an article about a topic you've been thinking about, or overhear a conversation about a thing that you yourself did just yesterday, and to conclude, ergo, I AM AT THE CUTTING EDGE OF A NEW AND POPULAR THING!

This magazine story includes a recipe for molasses cookies! And that guy at the store had a bottle of molasses in his cart! And I ate a molasses cookie for breakfast last week! That's three data points! Quick, someone set up a Tumblr and call the Times

and get a trend piece in the Sunday paper!

So I'm wary of drawing too many conclusions from my own biased, myopic observations. Nonetheless. There's something going on, the data points are widespread--the random people who write to me from the Netherlands and Bangladesh and Brazil (many of them young, I might add, lest you think this is just a nostalgic older-person thing) and the OED staffers and the esteemed

New Yorker writers (hello,

Roger Angell)--they're all over the place, people talking about letters and what a joy it is to send them and receive them.

Maybe it's a literary thing, specific to the bookish types whose days begin with Michiko Kakutani at the breakfast table and end with Gary Shteyngart in bed (... wait, that's not what I meant). People who love books, it follows, have specific romantic, wistful fixations on the printed word, and are probably--okay, damn near certainly--more inclined to hunger for handwritten letters, and to write them. There's certainly a common literary thread here.

Like: the publishing industry blog GalleyCat reported a few days ago that author Mary Robinette Kowal is launching what she calls

The Month of Letters Challenge--starting today, she and anyone else who joins the cause will send at least one piece of Real Mail every day the US Postal Service is in operation in February.

Like: The Rumpus, that proudly idiosyncratic online magazine of culture--particularly the literary variety--has taken the nascent trend and run with it, in their own way. They're calling it

Letters in the Mail. Five bucks a month gets you one every week or so.

Letter writers will include Dave Eggers, Tao Lin, Stephen Elliott, Janet Fitch, Nick Flynn, Margaret Cho, Cheryl Strayed, Marc Maron, Elissa Schappel, Wendy MacNaughton, Emily Gould, and Jonathan Ames. Think of it as the letters you used to get from your creative friends, before this whole internet/email thing.

The lede from

BookRiot's story on Letters in the Mail: "What's the next arena for literary foment? Try your mailbox."

But even if there is that bookish tinge to all of this, even if the most obvious data points come from this specific area of culture of which I am a more than part-time inhabitant, those data points, in the aggregate, arguably add up to something bigger, something more widespread. I fully support letters being the next arena of literary foment, but the more important thing is that they be more than just that.

IV.

Dave Eggers. Of course Dave Eggers is on that list--of course he's at the top of that list. Because, with all due respect, Mr. Eggers's very name has become a synonym for a certain aggressively earnest, calculatedly quirky, and--let's just say it--oft-grating flavor of modern culture. It's not that he isn't a brilliant writer (he is) and innovative publisher (ditto), it's that there's something uniquely maddening about Eggers-style culture, precisely because it wants to be so good for you, combining intellect with self-aware whimsy and then hard-selling it to you as a product, arch preciousness as packaged good.

And that's what kind of frightens me about the nascent rebirth of letters: I don't want this to be about nostalgia and wistfulness, alluring as they may be. I don't want this to be about affecting a specific pose, washed down with your neighbor's homemade craft absinthe to a retro-melancholy soundtrack of an intentionally-scratched EP by next year's South By Southwest darlings.

Letter-writing is about specific personal connection. That's the allure. I don't care if your envelope is made from a "Dukes of Hazzard" poster and the letter is about your inspiring corndog lunch with Rick Santorum. If you took the time to put pen to paper and shelled out forty-five of your hard-earned cents for a stamp, and made the effort to find a mailbox, I really do appreciate it. (Anthrax and epithets excluded, of course. Just to be clear.)

V.

My girlfriend and I met on the internet but fell in love over letters. Handwritten, sometimes handmade, old-school letters. Even though we lived in the same city and saw each other in person all the time, we sent letters (still do--Maren, check your mailbox). Sometimes we go for walks and one of us will say, "Oh, we have to stop by a mailbox so I can send this letter to you."

VI.

Is it just nostalgia? Is that why I like to write letters? Is that why other people are writing letters?

VII.

In part. Maybe. But I don't think so. And I sure as hell hope not because to a large degree, nostalgia is a wistful appreciation of something lost forever--it's a sequestering of that place or thing into the realm of memory, not present-day reality. It becomes self-pity: I wish I were alive in that time, doing that thing. But as, oh, everyone who has commented on nostalgia has pointed out, it paints a pretty picture, but not at all an accurate one. (I like modern medicine, I like not living in a time when state governors literally stand in the way of desegregation.)

My parents also wrote letters to each other in their courting days. My mother did a European Grand Tour for ten weeks in 1967 while my father stayed behind finishing up architecture school in Minneapolis, and the two sent letters to each other every two or three days. They've kept every last scrap of paper--letters, postcards, aerograms--in shoeboxes (literally, shoeboxes) for the last forty-plus years. (For anyone new here: this blog started as a means for me to document my own journey in my mom's footsteps, using those letters. Read all about it in my book coming out in April!)

As much as I'd like to pretend that everything my parents wrote to each other was dramatic and intriguing and elegantly-phrased (and written in quill-and-ink, on fine vellum), the truth is that much of it just isn't particularly interesting or quotable. They had a shocking disregard for the narrative-enhancing needs of the son they would have fourteen years later and who would grow up to be a writer. They wrote pages and pages to each other, but much of it was like this, from a letter Dad wrote to Mom in Vienna:

Gee whiz, Sil [they both called each other “Silly,” or, shortened, “Sil”], nothing out of the ordinary has been going on for the last couple of days. I know you've heard that all to [sic] often, which would sound like life is dull, which it is not at all. In fact, it is not even really routine. But the little things which make life interesting and wonderful seem trivial when repeated without the benefit of all the background. Let me see. What was my point. Oh, yes. In spite of its seeming—and necessary—sameness of school, work, and study it is not. I hope you follow, because compared to three months of travel this type of life could seem totally worthless, which it is not. Or maybe dull is a better word, which it still is not."

Or, just picking another letter sent to Vienna, there's this text-message-like note from Mom's sister, Susan, then a student at the University of Miami (all punctuation and spelling are hers):

speaking of the other u of m and homecomings and all that, yours was last weekend, and your friend and mine . . . yes, you know who, called . . . he was lonely for you . . . boy, was i sad for him . . . you wicked thing, what are you doing running around europe while he's playing solitaire on homecoming night? (don't you feel mean?) . . . anyway, i was really glad to talk to him, 'cause that was right when the plague was setting into me

Even more than travel or love, Mom and Dad wrote about the mundane minutiae of the day-to-day: missing library books, enrolling for classes, Dad's impending Air Force enlistment, a bus strike in Minneapolis, and Dad's current projects in architecture school. Much of the content was, quite frankly, precisely like today's Facebook status updates: comments on the latest local news, who went to what party last night, who ate what for lunch. The foundations of everyday life but not much of broader intrigue.

VIII.

No, it's not the content of our communication that has changed. It's the audience and the immediacy.

A postcard or a letter goes to one person—maybe a household, at most. It can't be forwarded with the click of a button. It can't be read in an RSS feed or on a mobile device by the whole world.

Writing to my father in 1967, my mother often drew little flowers next to her name or added additional comments along the side of a card. She sketched sheep and churches. Her handwriting was shaky when she was on a bus, large and loopy when she was trying to express a particularly important idea (usually, “I LOVE YOU”). She wrote on postcards, on wine labels, on tickets, on paper bags, on toilet paper. Dad wrote on aerograms (those sheets that fold into envelopes; here is an

aerogram template for you), on a long piece of drafting paper, on stationery from work. He sketched, too, including one card sent at the end of Mom's trip, with a forlorn Charlie Brown lookalike “welCOME BACK.” There was no concern for a catchy subject line. There were no links or embedded videos to pull the reader away. There were no ads on the side begging to clicked or pop-up chat boxes with salutations from bored friends-of-friends. It was not intended for a broad audience; it couldn't easily be cut and pasted or forwarded on to someone else. It was personal, the doodles and handwriting and surfaces providing an intimacy that blogs and e-mails simply cannot; it's the difference between dancing and lockstep marching or, more aptly, between a human and a machine.

IX.

The key, as I said, is a specific personal connection--and that's something that (I sure hope) knows no era and has no concern for trend. That's why my girlfriend, Maren, and I send letters to each other even though we see each other nearly every day--because it's a physical reminder of each other and our thoughts and our stories, a piece of ourselves that we can pin to a cork board or place on our shelves. It's a small handcrafted good that says, "When you weren't around, I was still thinking of you--and I made this for you."

It's the knowledge--or at least the presumption--that this particular person has written this particular thing to you. There's an implied intimacy there that can never be articulated in emails precisely because it is unspoken--it's about the act as much as the content. The effort and literal expense (money-wise but also time-wise) of sending a letter make a world of difference. This physical item was in the other person's possession, and now it is yours. There's a transfer of ownership--a gift of sorts, a memento. (I have a rather hard time imagining my mother saying, “Oh, just open my e-mail and do a search for the dates September through December 1967 and then read our notes!”)

Tactile, three-dimensional objects--especially letters, as manifestations of our ideas and personality and voice, captured in our unique scrawling writing--will, I respectfully submit, always be more ineffably soul-stirring than their pixelated, code-created counterparts.

X.

I want my own kids--whenever I have them, and no matter how digital the world has become by the time they grow up--to understand that, to agree. And to dance through through their own hallways on those frequent occasions when they receive a handwritten letter.

---

Notes:

1. If you send me a letter or postcard, I promise I will (a) do that happy mail-nerd dance when I get it, and (b) write back. My address is over there in the side-bar at right.

2. Many thanks to the various friends who have forwarded me the mail-related stories referenced in this post. Cheers, John Neely, Pam Mandel, Eva Holland, and Jason Albert.

3. N.B.: I make these points better, faster, and with more storytelling and less pontificating in the book.